Here’s the full text of my piece for kbbreview. The magazine suggested the topic – one with which I don’t entirely agree – and asked for 600 to 1200 words. Being me, I wrote, I think, 1196, which they edited to about half. This removed some of my argument.

It happens.

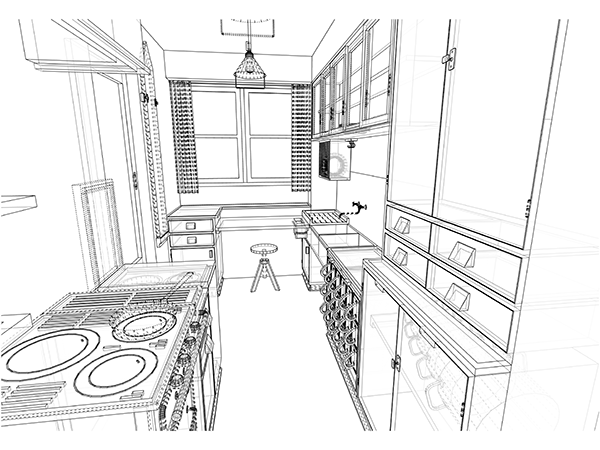

The illustration is my Sketchup render of an excellent free model of the Frankfurt kitchen.

“Somebody asked me why the kitchens industry doesn’t seem to produce iconic design pieces anymore.

Many universally-recognised design classics come from the middle of the last century, when for social and technological reasons new design was everywhere; the latest I can think of is 1990’s Alessi juicer. What is iconic kitchen design, and when if ever did we have it?

The original fitted kitchen is almost a century old. The Frankfurt kitchen aimed to improve women’s lives – because the kitchen in 1926 was very much a woman’s room – and as form follows function, its character, eclectic yet somehow homogenous, came out of utility: it was domestic engineering, for optimum efficiency. It was of a piece, too, for replication in cookie-cutter apartments.

Similarly original, I’d say, is the all-metal English Rose kitchen, which came about when WW2 aircraft manufacturers looked for postwar work. An English Rose kitchen is not of a piece but modular, its uniqueness in its cabinet profile. It probably helped that they didn’t have to worry about accommodating built-under ovens or integrated dishwashers, because there were none.

If there’s anything in recent decades approaching the social importance of the Frankfurt kitchen, it might be in accessible kitchens. Their mechanisms can transform lives, but we’re not going to see them on catwalks.

In 2013, an Italian-born designer in London exhibited the “million-pound kitchen.” It wasn’t vast: the money went on materials like crystal and copper. But as room design, its independent elements – an oven bank, a fridge bank, an island – reflected trends already well-established in kitchen design. Its biggest innovation was the price.

Perhaps the nearest single thing since English Rose to compare directly with an Alessi juicer or an Eames chair is the Smeg fridge. That’s hardly new. But innovation in kitchen design often comes as technology: the Bora downdraft hob, the downdraft extractor before it, even the Quooker tap, have changed what we can do in kitchens and how they can look. Each caught on so well that they became ubiquitous perhaps before we had time to recognise how special they were. But they only have meaning as parts of a whole kitchen: if we want to find single pieces we can call iconic, we might have to look at taps or island extractors – examples of design in a kitchen, not kitchen design.

Fitted kitchens are not often of a piece. A juicer or a chair can be dropped into any room; almost every kitchen has to be designed new, for its particular space. Perhaps what can be considered iconic in kitchen design is not a piece, but a style.

I’ve been told that Siematic missed a trick by not patenting the original “gola” true-handleless principle, and that their new version, mitred with integrated lighting, is an attempt to correct that. True-handleless is a revolution, redefining every cabinet, and although it’s far from new worldwide, it’s still finding its way into the UK mass market, along with the new technical demands it imposes.

Also from the mainland – I suppose we call it Europe again now – comes a neo-brutalist, secret kitchen look we associate with certain Italian and German brands, like Poggenpohl. We walk around a cube of stone to find it’s an island; we slide a concrete panel aside to reveal ovens and a sink. Boffi takes this even further into a loft-cum-factory-styled environment. These looks lean heavily on sliding and pocket door technology, which will surely be the next thing to reach the mass market: if pocket doors aren’t at Wren yet, they will be. Again, the aesthetic depends on the technical.

Germany also brought us openness to new materials, and a different way of seeing: we’re not as afraid of space or texture. Using all these ingredients, certain studios – I’m tempted to call them kitchen design houses – offer “house styles.” We can recognise a Sola kitchen on sight; we can look at Roundhouse’s new Richmond showroom and tell that Roundhouse designed it. Even an IKEA kitchen we can spot a mile away. Sometimes just a texture catches on, like the current fever for flutes and acoustic slats.

Do we have standout “piece” designers, our Starck or Eames? Not so much. We have celebrity endorsements. We have Clive Christian and the heirs of Mark Wilkinson, drawing on old styles for new kitchens. We have Johnny Grey, working a kind of organic retro-futurism big on curves. It’s not for everyone, but Hampshire’s ELK takes kitchen cabinetry and literally turns it on its side, or on its corner, yet is somehow still Art Deco.

Elfin Kitchens compress whole rooms into single cabinets, calling back to Frankfurt’s hyper-efficiency, but lack glamour. Walk-in pantries too quote old times. If there is an opportunity for replicable, single “wow” pieces, it must be islands.

The island itself is unique to kitchens, derived from the open plan. Moiety’s floating islands are hard to forget, once seen. Poggenpohl has a signature island with an offset top. Many of us could come up with a distinctive island – a Corian egg, say, or a sailing ship in marine ply – and it would be nice to sell the same idea forever, but unless people like and buy it, it’s going nowhere. A few years ago, Wren introduced some angular, character islands which, despite exposure, failed to catch on. It may have been a context error, the cost too aspirational for the clientele.

We’re salespeople. We design not for galleries, but for our domestic clients, with their tastes and rooms and budgets. We are sales-led and client-led, not design-led, and few enjoy such status that we can sell something truly original on the strength of our name. There’s a small upside: the purchaser of an Eames chair doesn’t get to say, “It was designed for me,” while every kitchen buyer can.

Not that originality is easy. For years I nurtured my great idea of a Mondrian-inspired kitchen, then I saw it at Naked Kitchens. Damn.

And we copy. While there are studios vocally opposed to imitation, they use other people’s solutions themselves, because you can’t reinvent every wheel. There can only be certain ways to combine integrated dishwashers with extruded plinths. It’s said that you can’t copyright an idea: Bora’s hob wasn’t unique for long, and Halcyon has its own floating island in Wigmore Street. Everybody has some version of true-handleless. Some time ago, struck by the way Stoneham used LEDs to outline a kitchen, I copied it. Whether we call it theft or inspiration, we all do it, and today’s icon becomes tomorrow’s standard.

Iconic design doesn’t announce itself so much as it’s announced to us. Because every kitchen is a new start, somebody might be coming up with something inspired anywhere, at any time, without publicity. The key word in the question could be, “seems.” We might be surrounded by iconic design, and just don’t get to see it.

Or perhaps the question is just impatient. English Rose came twenty years after Frankfurt. The next iconic piece might be around the corner. I can’t imagine what it might be – but that’s kind of the point, isn’t it?

I really want to do the egg island now, though…”